In recent years if you have watched men’s professional tennis it would be hard not to notice Rafael Nadal’s return position. Always a defensive-minded returner, Nadal has shifted so far towards the back on the return of both first and second serves that he is sometimes not even visible to the cameras. It is not inherently a bad idea. For Rafa, this fits into a larger strategy that allows him to play more points on his own terms. It helps him make the tennis match about the things that he does well. This does not however make it a good idea for everyone, or as we will see, for all situations.

When you decide where to stand to hit the return, you are deciding the terms on which the point will start.

Horses For Courses

The World Tour Finals in recent years have been played on indoor hard court in the O2 Area in London. It is about as opposite an environment to the center court at Roland Garros as exists at the top tiers of men’s professional tennis. The courts typically play quickly, and as is always the case the indoor conditions favor more attacking tennis. The conditions require many players to alter their strategy in the same way that the conditions at the French Open do – any player whose natural tendencies are not suited to more attacking tennis typically must adapt or fail.

The return philosophy is a critical part of any strategy.

Where a player returns from is a critical part of their return philosophy.

Ideally on faster indoor courts a player would stand higher up in the court, closer to the baseline. They would seek to take time away from their opponents, and look for opportunities to move forward. Anyone who wants to stand far back during rallies and wait for errors is going to have a difficult time in these conditions. We’ve established that the return position dictates the terms on which the point is going to start, so the return position should follow suit. It should be cohesive with the rest of a successful strategy for the playing conditions. The second serve in particular is an opportunity for the returner to choose the terms of their return.

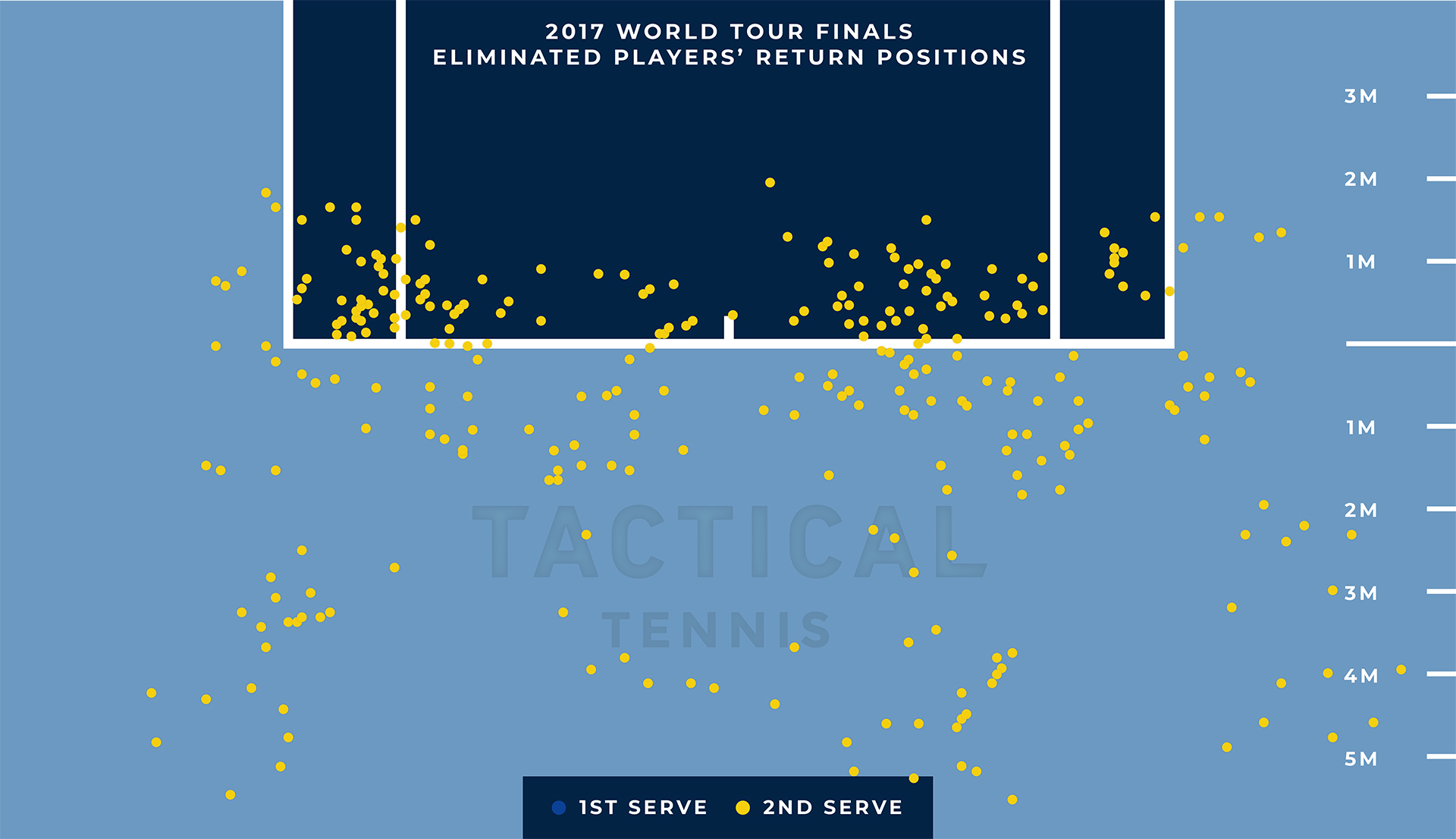

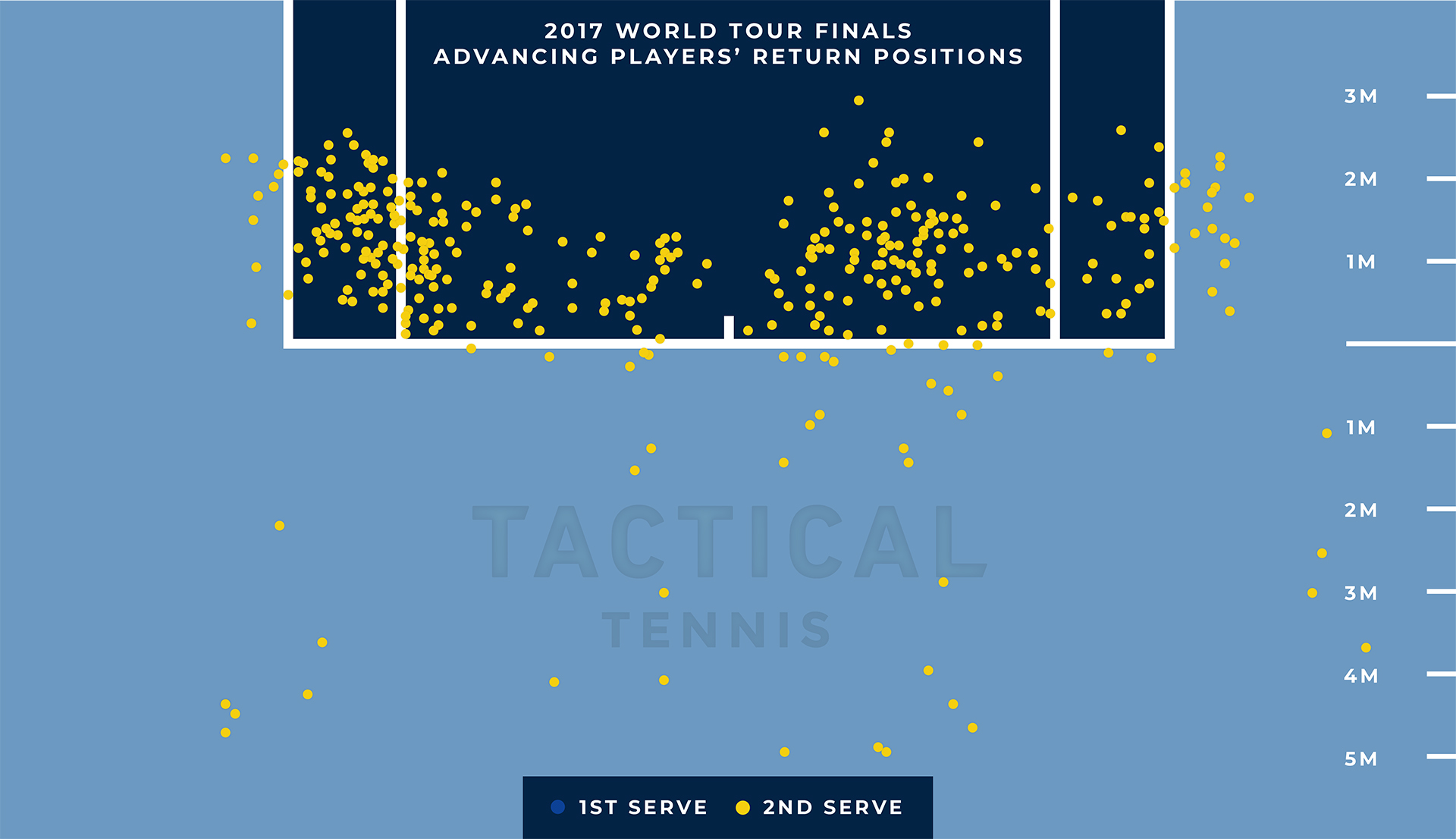

When we look at the return positions of all of the players in all of the matches at the World Tour Finals in 2017 on the second serve, there are some very clear messages. Return position was a huge predictor for success of the participants – and there were some surprise successes during this particular tournament.

Adapt Or Die

The World Tour Finals has two round robin groups of four. Everyone within a group plays each other, and the top two players from each group advance to the semi-finals. The other four players go home.

Each dot in the image above represents where the returner made contact with the ball on their return. The players who were eliminated all had something in common – a lack of a cohesive return strategy. It’s not that they didn’t each have a return strategy, it’s that the strategy they employed wasn’t suitable for the conditions they were playing in.

This is easily seen in the image. The contact points are all over the place. While some of the players stepped up and took the return early some of the time, none of them committed to doing so for the entire tournament. And those dots that are 4-5 meters (12-15 feet) behind the baseline? That’s mostly Nadal and Thiem. It’s probably worth noting that there are two major titles Nadal has never won – the World Tour Finals, and the Paris Masters. Both are played on faster indoor courts. Coincidence?

If this is what the return position looks like for the players who were eliminated looks like, how about the players who advanced past the group stage?

Stealing Time

The pattern is immediately clear. The players who advanced stepped up and took the ball early. They stole time from their opponents. They committed to playing fast and aggressive tennis. Most importantly, the people who won returned in a way that fit into an overall strategy that was suitable to the conditions of play. As it turns out, for each of these players this wasn’t a shift from their normal approach to returning. Goffin, Federer, Dimitrov, and Sock all regularly prefer to take the ball early on the second serve return.

You may have noticed, and wondered about, that small handful of deep return positions on this graphic. All but one of those are Jack Sock – whose entire game is built around probably the biggest forehand in the sport of tennis. Sock will occasionally stand deeper in order to run around his backhand on the second serve and clock a forehand as his first ball of the point. For Sock this still fits into his cohesive strategy, as his backhand return is generally of far lower quality, and his forehand is big enough that he can immediately step up into the court and maintain his aggression.

The one data point that wasn’t Jack Sock? It was Roger Federer, doing exactly the same thing.

The Power of Cohesion

Looking at this data brings some interesting things to light, but more importantly it raises interesting questions for any tennis player. As the game has continued to evolve (and the players with it), we have seen fewer and fewer so-called ‘surface specialists’ compared to the eras of the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s. Increasingly players have had the tools to compete on all surfaces well. However there are still limits. Players still have preferences. Nadal has never approached his level of clay-court success on other surfaces. There are many players successful on faster courts who seemingly have never figured out the clay.

It would be simple, and perhaps lazy, to write this off as a lack of tools. With Nadal’s successes at the Australian Open, Wimbledon, and the US Open can we really say that he lacks the tools to be as successful on hard courts and grass courts as he is on the clay? Or is it rather than Nadal stubbornly clings to his clay court strategies and simply imposes them onto other conditions to which they are not as well suited? It is no coincidence that Nadal’s only successes at the US Open have come when he’s committed to playing (and serving) more aggressively.

Do you have a truly cohesive strategy for your tennis game? Does the way you serve fit with the type of point you expect to play? Does the way you approach returns? What adaptations are you making to different surfaces and opponents? The more you can take all of these different pieces that make up your game and make them work together, the more matches you are going to win.