Introduction

Athletic movement is a critical difference maker in tennis performance. It is also one of the areas that players struggle to improve the most. Movement patterns are learned and habituated at a young age. Most players develop their physical capabilities (strength, explosiveness) as the pathway to better movement. This neglects the technique component. Understanding the universal athletic component is a critical piece of movement technique.

Tennis requires a greater adaptability in movement than almost any other sport. A tennis player must be able to react explosively in all directions. While other sports also have this requirement, few demand this capacity in such a wide variety of circumstances.

For reactive movement in tennis, only the return of serve offers us an opportunity to reset. During a point we must constantly adapt our positioning, and the demands of the movement are changing.

As such, it becomes important to be guided by principles rather than rules. Understanding the essence of good movement gives us the ability to adapt our movement to the situation in front of us. What constitutes a perfect split step changes depending on where in the court we stand and our direction of travel.

Ultimately we are guided by three key needs:

1. Balance

2. Explosiveness

3. Directionality

The Universal Athletic Position

All movement begins somewhere. The position that we begin from influences the movement that follows. The better the starting position, the better the potential for the movement. Our starting position should allow us to be balanced, to generate power efficiently, and to move athletically in all directions.

Enter the Universal Athletic Position.

The Universal Athletic Position (UAP) is so named because it is the most common position in sports. While there are sports that don’t feature the UAP at all, most land-based sports feature some version of it in at least some aspects of the sport.

We don’t train and use the UAP because it’s in most sports though. It is in most sports because it is the most efficient stance to be able to react explosively in all directions. That’s what makes it universal. More specialized sports that feature limited dimensions of movement will tend not to feature the UAP. However sports that require reaction in multiple axis of movement (baseball, tennis, basketball, soccer, cricket, among others) all see usage of the UAP at the highest levels.

How does it address our three primary needs?

Balance

Balance and stability go hand in hand. The more stable a stance, the less athleticism required to remain balanced in it. An athlete standing on one leg on an uneven surface faces greater challenges than one with a wide stance on a flat surface.

Primary things to note here are stance width, posture, and weight distribution. Generally, the wider the stance, the more stable it becomes. Past a certain point that stability becomes counterproductive. An athlete in the splits will not fall over, but also cannot move very quickly. We should aim for a stance wide enough to provide stability (heels outside the hips) without compromising movement (narrow enough we can comfortably bend at the ankles, knees, and hips).

Good posture doesn’t always mean standing upright. It does mean good spinal alignment. Across sports we see great movers keeping their spine erect even as they have flexion in other joints.

Finally weight distribution. We should strive to have as much of our foot in contact with the ground as possible when our direction of travel is uncertain. Different movement directions require applying force to the ground through different parts of our feet. If an athlete is on their toes, they cannot utilize their heels for movement without first putting their heels down – costing valuable time.

Explosiveness

If we consider peak explosive movement from a stationary position, we can take cues from great jumpers. There is a significant overlap in the muscles used for a standing jump and those required for explosive movement laterally, forwards, or backwards.

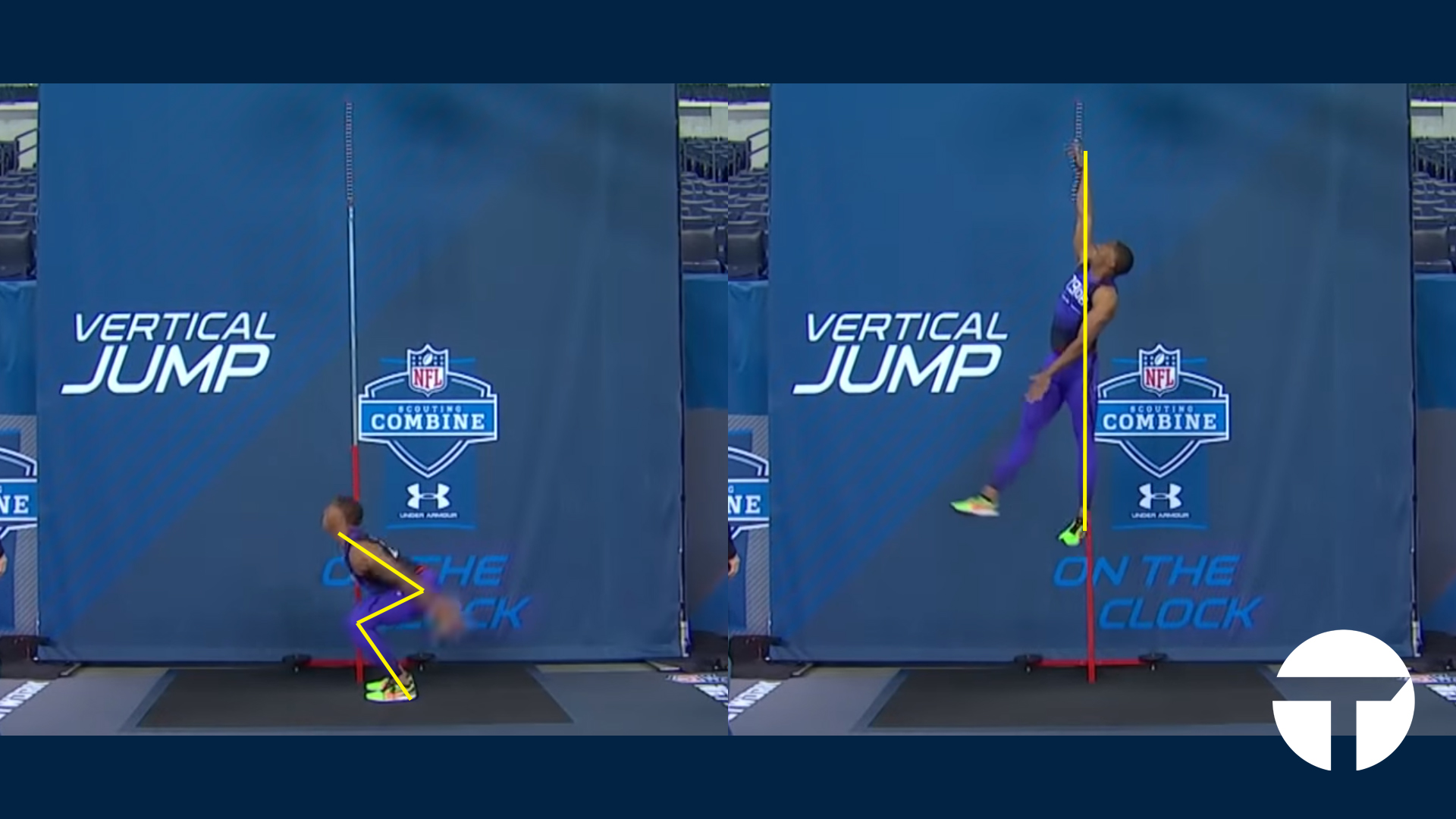

Byron Jones set an NFL combine record for the standing jump. His goal (and that of any great jumper) is to recruit as many useful muscles as possible towards upwards propulsion. We can see he engages flexion at the ankles, knees and hips. This allows him to use all of the powerful muscles involved in extending those joints to launch himself upwards.

We want to follow a similar path. A good Universal Athletic Position will feature the same patterns of flexion, just to smaller degrees. We should have bends at the ankles, knees and hips to utilize our quads, hamstrings, glutes, and calves to maximum effect. Where a tennis player differs from a great jumper is in the amount of flexion and the width of the stance. A tennis player must compromise their potential jump height to allow for the third criteria: directionality.

Directionality

All of that force we generate is useless if we cannot direct it in the appropriate direction. Thankfully, there is a large overlap between the demands for balance and those of directionality. As our stance narrows it doesn’t simply make balance more challenging – it limits our ability to apply force in any direction other than upwards. Widening our stance to outside of our hips lets us use a combination of extension, abduction, and adduction across our two legs to move forwards, laterally, or backwards.

Additionally we can manipulate our weight distribution to allow even more direction of our generated force. An elite athlete will initiate a controlled fall to align their body better with their direction of travel. In a wider stance, lifting our left foot and allowing a degree of falling to the left allows us to better drive force in that direction.

Putting It All Together

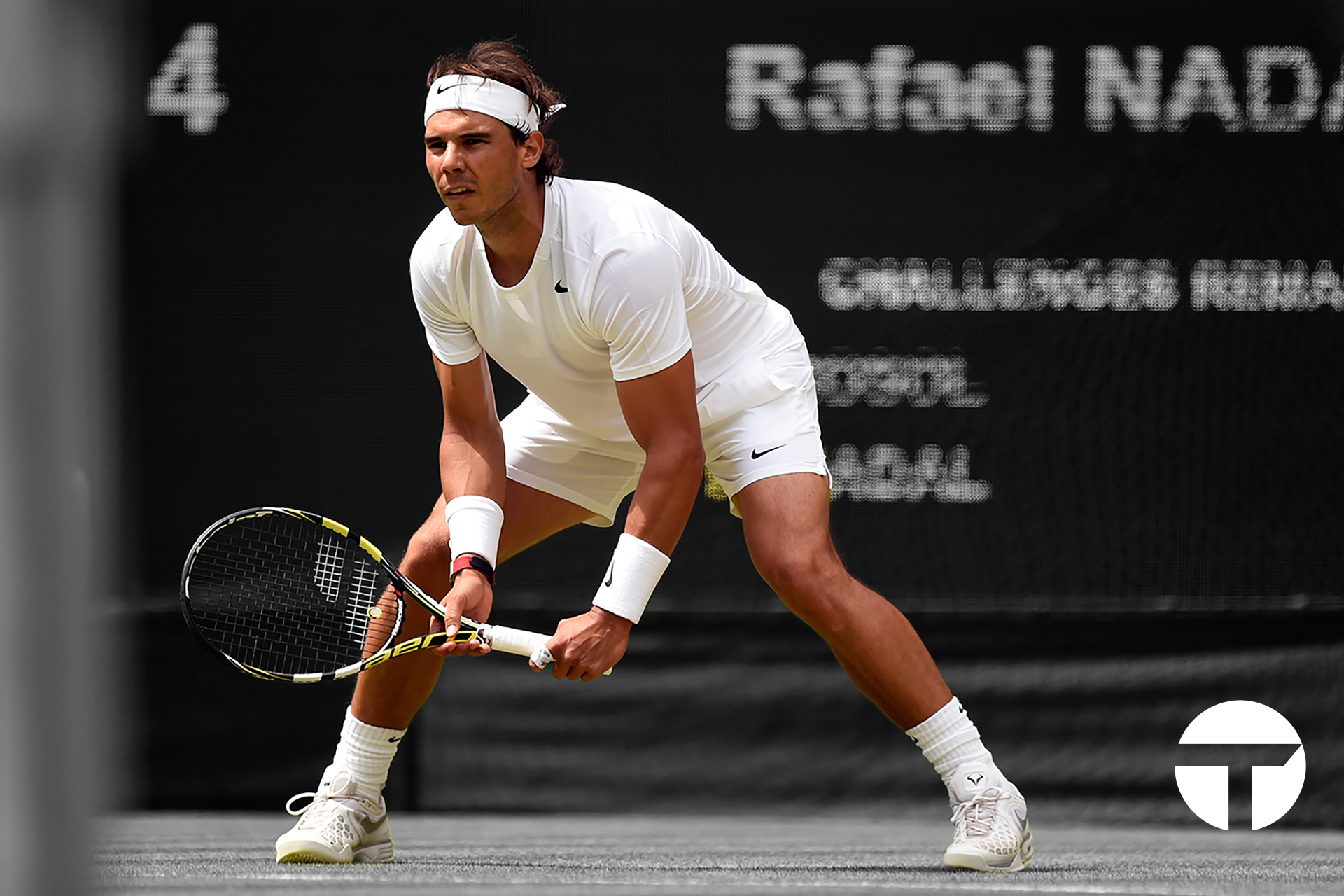

This brings us to the finished product. A tennis stance where our feet are wider than our hips without limiting hip and knee flexion. Where we engage flexion at the ankles, knees, and hips for maximum force production. Where we keep good posture, to allow better control of our balance.

In highly contested points, a player might only attain a complete Universal Athletic Position once (as the returner) or possibly not at all (as the server). However great tennis athletes are always moving towards a Universal Athletic Position. They will obtain (or retain) as much of it as possible even as they move dynamically around the court.

When we understand the principles behind a position rather, then we can strive towards those principles. This helps guide our movement in non-ideal situations. We can move away from a binary way of thinking about movement technique (either you reached the position or you didn’t) to something more sophisticated (I retained as much of an ideal position as possible).

This is a path to better movement, and better tennis.

For more content follow us on instagram, facebook, and tiktok!